This one's about the paper that shows a probable mouse origin for Omicron

From humans to mice to humans or simply mice to humans? That is the question.

So you may or may not be aware that there’s a paper that was published on Christmas Eve that explored the phylogenetic evolutionary history of Omicron. It is entitled: “Evidence for a mouse origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant.” I put this phylo tree image here because I wanted it to be the thumbnail. It is explained at the end. Although, it doesn’t really need an explanation.

In this paper, they looked at 45 pre-outbreak Omicron mutations that occurred since divergence from the B.1.1 lineage. Many of these point mutations occurred in the spike (S)-gene. What is probably the most interesting thing that they found was that there was over-representation of nonsynonymous mutations in Omicron ORF S because this, as they point out, suggests strong positive selection. Positive selection is a natural process in the biological evolutionary process where new advantageous variants take over a population. In this particular case, the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of the spike protein of the SARS-nCoV-2 evolved to become more ‘bind-a-licious’ with the ACE-2 receptor in mice. Here’s a figure from the paper showing the Omicron mutations.

Twenty-six of the 27 pre-outbreak mutations in the ORF S of Omicron were nonsynonymous resulting in a dN/dS ratio of 6.64, significantly greater than a dN/dS of 1.00.

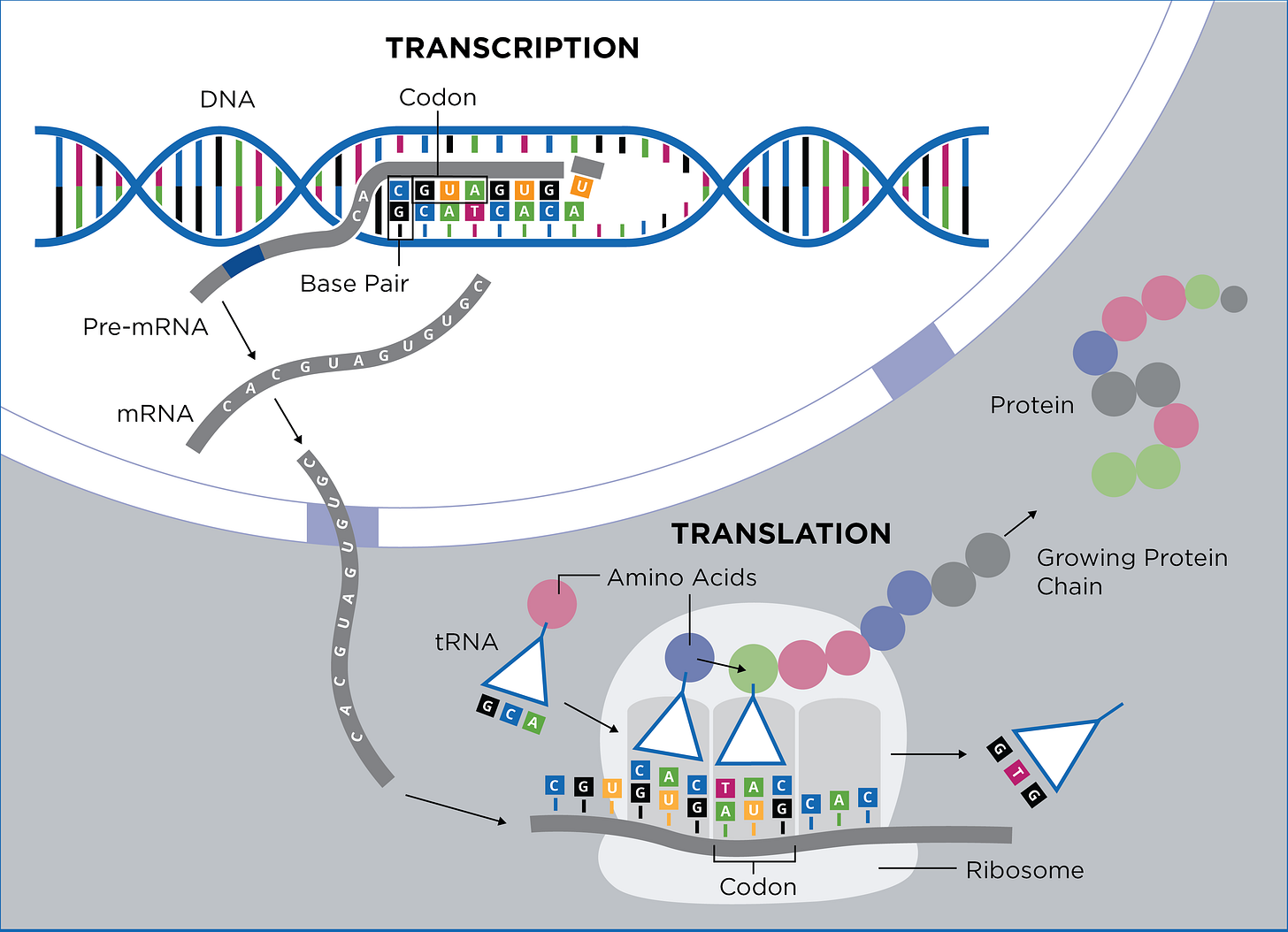

What? ORF? Non-synonywho? An ORF is an Open Reading Frame - a section of DNA/RNA text in between a promoter and a start and stop codon - the ‘open’ part means there are no stop codons in the ‘reading frame’.

The ORF contains a bunch of DNA codons that will ultimately result in the production of a functional protein. Ribosomes can read sections of RNA text until they run into a stop codon which is the indication to stop. Protein made! We need these otherwise, how would we ever have proteins? Genes, mRNAs and roteins have beginnings and ends too! Did that make sense?

In order for any of the other stuff I wrote to make sense, we have to understand the difference between synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations.

Synonymous mutations are point mutations. This results in a change in one base pair in the RNA copy of the DNA. In the following picture, the point mutation causes a change in the nucleotide base pair resulting in a swapping of amino acids - in this case from glutamine to valine when T is replaced with A. A synonymous mutation occurs when the nucleotide changes but the amino acid does not. These are also referred to as silent mutations. A codon in RNA is a set of three nucleotides (like CTA - cytosine, thiamine and adenine) that encode a specific amino acid like Leucine. There are four bases in our DNA: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thiamine (T) and for RNA, there’s also uracil (U).

Proteins are not affected by synonymous mutations and they have no real role in the evolution of species since the gene or protein is not changed in any way. Synonymous mutations are actually fairly common, but since they have no effect they do not affect.1

A nonsynonymous mutation results in the amino acid changing or even affecting the read of the codons or inducing a stop to the read altogether.

During transcription when the messenger RNA is copying the DNA, if there is usually an insertion or deletion of a single nucleotide in the sequence then this can result in a nonsynonymous mutation. This single missing or added nucleotide can causes a ‘frameshift mutation’ messes up the codon triplets themselves. This This can result in an amino acid being swapped out for a new one and thus can change the protein that is ultimately expressed. It is interesting that the earlier this type of mutation occurs in the sequence, the more severe the mutation. It could even result in a lethal mutation. Nonsynonymous mutations can also induce positive changes with regards to favorable adaptation from the mutation and can also increase the diversity in the gene pool.

So in this case, the authors claim that most of the mutations were positively-selected for changes in amino acids that selected for a receptor binding domain in the spike protein that binds the ACE-2 receptor in mice better - probably with higher affinity. Geez. I hope I got that right.

This is too heavy.

Counting mutations across the whole SARS-CoV-2 genome indicated that Omicron acquired mutations in the genome at a similar rate to other variants, suggesting that the accelerated evolutionary rate of ORF S could not be explained by an overall elevated mutation rate in Omicron progenitors. In light of these findings, we hypothesized that positive selection could have helped accelerate the evolutionary rate of ORF S.

So what this means in a nutshell is that it is likely that the Omicron mutations were probably generated in the context of a mouse based on positive selection and not solely on elevated mutation rate in Omicron precursor relatives. Does that make sense?

Here’s a figure from the paper that shows how the interactions between spike and ACE-2 in different mammals were different with statistical significance. Mus musculus is the common house mouse. Poor mice.

So this figure shows statistically significant enhanced interaction by spike mutations in Omicron in mice, humans, camels, wolves and goats. So they claim that based on the higher ACE-2 ‘interactionability’ with the mouse ACE-2, it is highly likely that the many mutations in the Omicron spike RBD occurred in the context of the mouse house of mutations, and not in the human house of mutations.

We found that, compared with the RBD encoded in the reference genome, the Omicron RBD showed the highest ACE2-interaction enhancement with mice among all these mammals (Fig. 6), suggesting that mice were the most likely host species to influence the evolution of the progenitor of Omicron.

Alright, this paper is really heavy so let’s take a break. Let’s dive into Nextstrain’s phylogenetic tree awesomeness.

I think phylogenetic trees are really cool. Let’s take a look at Omicron’s phylogenetic evolution over time in the context of say, Delta using Nextstrain.

The claim of the paper is that the Omicron variant went from humans to mice back to humans. This is plausible. If you look at the above figure, you can see that this timeframe spanning the spring of 2020 and the fall of 2021 looks like when the mutations in the RBD might have occurred in the house mouse. The question then becomes, where and when and how did it find it’s way back into humans?

Question: Is it possible that the Omicron variant came directly from mice? Where have I heard of Mus musculus being used before?

Scoville, Heather. "Synonymous vs. Nonsynonymous Mutations." ThoughtCo, Jan. 26, 2021, thoughtco.com/synonymous-vs-nonsynonymous-mutations-1224600.

i love you Jessica. Keep fighting the fight

I suppose that it's time someone said curiouser and curiouser again.

This guy went down the rabbit hole several weeks ago.

https://igorchudov.substack.com/p/omicron-as-a-bioweapon-thoughts-and