Phenotypic mixing, tropism enhancement and recombination - implications of a lab engineered 'virus' mixing with the existent coronavirus 'swarm'

Some questions asked about what we might be dealing with and where it came from...

This article has been in the making for over a week now. It comes on the heels of a pre-print submission of an article that I summarized here. To briefly summarize the summary, recombination techniques were used to create a new terrible version of SARS-CoV-2 using the ‘backbone’ of the original chicken recipe Wuhan with Omicron spikes embedded in its membrane, to make a new chicken version with an 80% mortality rate in mice. The part about this that bothers me is not so much the part about the mortality rate in the mice, but the part where they are doing this in the first place. Reading about work like this makes it far more easy for me to imagine that this SARS-CoV-2 virus was engineered in a lab from the get-go.

I would be remiss if I did not summarize this even more recently uploaded pre-print entitled: “Endonuclease fingerprint indicates a synthetic origin of SARS-CoV-2” that was uploaded to the bioRxiv pre-print server yesterday, October 20, 2022.

And please read this Substack article: it’s a brilliant summary of the pre-print, and also a ‘how to’, for restriction enzymes.

(Look up infectious clone technology.)1 And read this paper: “Rapid reconstruction of SARS-CoV-2 using a synthetic genomics platform”.

During the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, virus isolates were not available to health authorities and the scientific community, even though these isolates are urgently needed to generate diagnostic tools, to develop and assess antivirals and vaccines, and to establish appropriate in vivo models. The generation of the SARS-CoV-2 from chemically synthesized DNA could bypass the limited availability of virus isolates and would furthermore enable genetic modifications and functional characterization.

WT SARS-CoV-2 has no deficit in terms of viral RNA species produced, plaque morphology, or replication kinetics. Therefore, it might be used as an equivalent to the clinical strain.2

What this means is that they didn’t have the virus to play with so they made an excellent lab equivalent. The question is: WHEN did they do this?

The pre-print provides strong evidence (which I have known about for a time now thanks to many merry mates) that SARS-CoV-2 was engineered based on the locations of what are known as restriction sites within the genome, and also, the subsequent sizes of the DNA fragments. The presence, absence and locations of these restriction or cutting sites (you can think of these sites as place holders to enable copying and pasting of differential DNA fragments), is the equivalent of a fingerprint and can be used to ascertain whether a virus is synthetic or not. The authors of this pre-print found that the restriction site fingerprint for SARS-CoV-2 - which is typical for synthetic viruses - “is anomalous in wild coronaviruses, and common in lab-assembled viruses”.3

Both the restriction site fingerprint and the pattern of mutations generating them are extremely unlikely in wild coronaviruses and nearly universal in synthetic viruses. Our findings strongly suggest a synthetic origin of SARS-CoV-2.

My pending research questions:

If recombination (or in vitro genome assembly or reverse genetics system/infectious clone) techniques were used in a lab context to create a hybrid HIV-1/SARS virus (for example: a coronavirus with HIV peptides embedded in spike surface glycoproteins) then would phenotype mixing in vivo (in HIV-infected humans, say) allow for tropism enhancement of this hybrid virus?

Could macrophages be the shared cell type for infectivity to enable phenotypic mixing?

Would this hybrid be capable of infecting CD4+ T cells?

Would this enhanced virus be readily transmittable to others via the SARS route (nasal/air)?

…Some background that you can skip if you like…

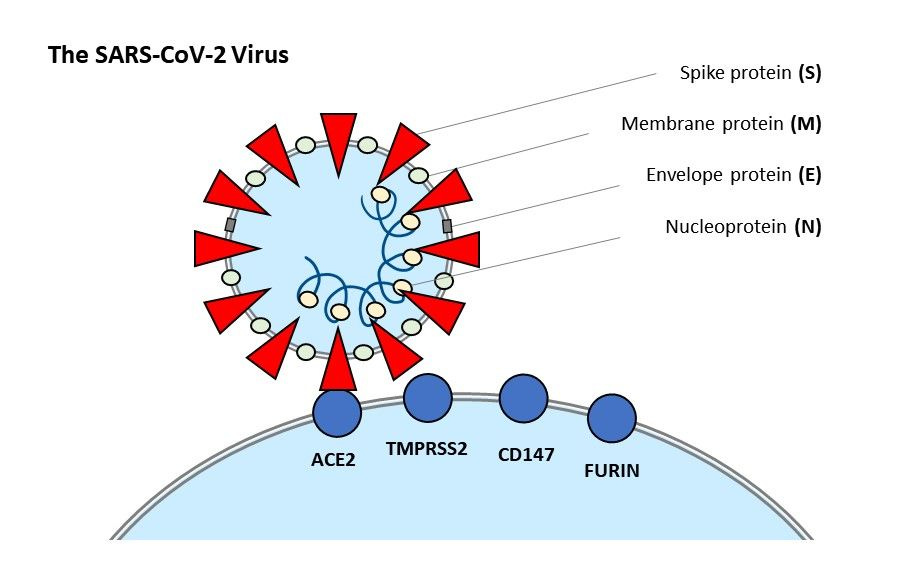

On viral membranes (and lipid rafts) and membrane glycoproteins

Viruses can be enveloped, aka enveloped viruses, or naked. Ooh la la. Enveloped viruses are covered in a functional protective membrane (I will be referring to this as a ‘coat’ later on in this article) that is often embedded with viral membrane-bound glycoproteins. For example, the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoproteins are well known to most of us by now: they crown these viruses and hence the name “corona”virus (from the Latin corona “a crown, a garland”4).

The membranes of enveloped viruses are primarily host-cell derived. For example, upon cell egress, the HIV virion is encased in the host cell membrane and pinched off to be released to the extracellular environment in a process called budding. Budding is associated with lipid rafts that lie within the cell membrane. Lipid rafts are free-floating membrane microdomains that are tightly knit and full of glycosphingolipids, cholesterol and protein receptors. Lipid rafts have been suggested to potentiate steps of the viral life cycle such as virus entry, assembly, and budding.5 SARS-CoV-2, especially Omicron, uses lipid rafts for cell entry via endocytosis.67

Viruses, like SARS-CoV-2, can also exit cells via exocytosis.8 This involves the pre-packaged virus being delivered in endosomal compartments to the cell membrane for egress called the lysosomal exocytosis pathway.

The reason I make mention of membranes is because I am wondering about the ability of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus to 'house' other types of glycoproteins in/on its membrane surface. To me, it would depend on the specific membrane components and on whether or not the non-native glycoproteins could physically be embedded in the membrane - would they embed partially or be trans-membranous? I didn’t use HIV-1 and SARS-2 as examples by accident. There are actually many similarities between these two viruses - and not simply structurally. Of course, there are major differences as well!9

As a conclusion, we would like to point that although at first sight these viruses do not resemble each other, the molecular mechanisms used are common: the increased of pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesis, the modifications in intestinal microbiota, the NETs formation. (Reference #5)

The main things that you need to know for the purposes of this article (not even sure what that purpose is anymore) are that SARS-CoV-2 and HIV-1 are both enveloped viruses with surface glycoproteins - spike and gp160 (env-glycoprotein complex), respectively, and that they both abscond their membranes from the host cells that they infect. They also both use fusion machines (envelope proteins of HIV and spike protein of SARS-CoV-2) to gain entry to cells by viral-cell membrane fusing.

The envelope of Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 (HIV-1) consists of a liquid-ordered membrane enriched in raft lipids and containing the viral glycoproteins.10

Overall, the HIV-1 lipid composition is typical of lipid rafts.

N.B. SARS-CoV-2 can also enter cells using endocytosis.

The CoV envelope (E) protein is a small, integral membrane protein involved in several aspects of the virus’ life cycle, such as assembly, budding, envelope formation, and pathogenesis.11

Here’s a nice animation of what viral-cell membrane fusion looks like. Lipid rafts not included in animation.

On phenotypic mixing

The word phenotype comes from the Ancient Greek φαίνω (phaínō) 'to appear, show, shine' and τύπος (túpos) 'mark, type' and describes the traits of an organism. The traits in the biological context are the observable features of the organism. Phenotypic mixing can happen when say, two viruses get together to exchange ‘coats’. See, I told you I would refer to coats.

In the following cartoon in Figure 3, the embedded coat components of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV are shown. On the left is a spike trimer (three identical bits called monomers) from SARS-CoV-2, and on the right is the gp120 glycoprotein from HIV.12 They are both viral surface proteins that mediate attachment to target cells. Structurally and mechanistically, these receptors are not dissimilar: they both attach to respective receptors/co-receptors on specific cell types using exposed extra-membranous components (S1 on spike, and gp120 on HIV) to induce conformational changes to expose the trans-membranous components (S2 on spike, and gp41 on HIV) that are subsequently used for membrane fusion and dumping of viral genetic material into the cell resulting in ‘infection’ of the cell.

You can think of the viral genetic material as the guts of the virus, and the surface proteins embedded in the membrane as the coat, as I mentioned.

What is really important to understand here is that phenotypic mixing is a particular type of ‘coat swapping’ that does not involve an exchange of genetic material. The proteins on the membrane surfaces can be exchanged in the absence of genetic material getting involved. I sometimes think of this as ‘plug and play’ type activity and visualize zip drives being swapped between machines with different operating systems. But let’s personify this, shall we?

Let’s imagine we’re at a big party. Coat swapping at a big party in a dome-shaped venue is probably an accurate personification of phenotypic mixing between viruses in a cell. Most of the people at the party are likely similar enough to be able to wear any other party-goer’s coat. Let’s imagine, that when people leave the party, they can take someone else’s coat from the coat check. They might even be lucky enough to grab a mink coat - a coat that might allow them VIP access to the next big fancy party. But, even though they might be able to use that fancy coat to get into that party, they will not be able to wear that coat inside ad infinitum because the owner of the coat might recognize it and yell ‘thief!’, or maybe the smell of perfume on it would lessen chances to find a ‘mate’. For whatever reason, before socialization at the next VIP party can occur, that mink coat must be swapped back to the coat that the VIP party-goer normally sports. Let’s say it’s a jean jacket. I really don’t know if this made any sense.

Getting back to viruses, picornaviruses (Foot and Mouth Disease Viruses (FMDV)) do this coat-swapping and also Rhabdo- (Vesicular Stomatitis Indiana Viruses (VSIV)) and Paramyxo- (mumps, measles and human parainfluenza) viruses can accomplish phenotypic mixing, even though these viruses are genetically unrelated.

The outcome of phenotypic mixing is an ability of a virus to infect other cell types due to new cell surface receptors. Because this event does not involve genetic material, the progeny lose this enhanced infectivity, as indicated by the necessity to lose the mink coat and revert to the jean jacket before socializing as part of the mating ritual.

Let’s go back to HIV and SARS-2 as examples. Phenotypic mixing between these two viruses, if it was possible, could mean that a SARS-CoV-2 virus could acquire HIV surface proteins (or that an HIV virus could acquire SARS-CoV-2 surface proteins) and thus would theoretically be able to infect CD4+ T cells, in the former example, temporarily. These ‘mixed’ viruses would reproduce using host cell machinery, but their progeny would only retain the original SARS-CoV-2 surface proteins, meaning that the progeny would lose their ability to infect CD4+ T cells. However, the damage to that particular cell would be done. In the case where HIV absconded SARS-CoV-2 spikes, these virions could infect all cells with ACE-2 receptors. What a total disaster that would be. This, theoretically, would allow HIV to integrate its genome into the host cells’ genomes and subsequently, whenever these cells became active, HIV virions would be produced en masse.

Besides wanting to know if this could happen in the first place, I would also like to know what would happen (if this phenotypic mixing event did occur) if enough of these phenotypically mixed SARS-CoV-2/HIV viruses come into existence within shared cell types, could they subsequently be released and transmitted to another host? And if so, what would be the effects of this? Would these virions be capable of infecting the CD4+ T cells in a new host, irrespective of HIV status, for example?

On tropism

Viral tropism is the ability of a virus to productively infect specific cell types or tissues in a particular host.13 It defines to whom and how the virus does its thing, basically. For example, the tropism of HIV-1 renders it able to infect CD4+ T cells via the CD4+ receptor and either the CCR5 or the CXCR4 chemokine co-receptors. The tropism of SARS-CoV-2 renders it able to infect a multitude of cell types and tissues via ACE-2 and CD147 receptors as part of the human respiratory tract, conjunctiva,14 kidney, liver, adrenals15 and more!16 One might argue that SARS-CoV-2 is tissue tropic for all human tissues: it appears to be.1718

In the case of phenotypic mixing, it would be like transient tropism enhancement.

As an aside (sort of), it’s been shown that viral tropism is partially dictated by the presence of type-I interferons19 and this is particularly interesting since it has also been shown that type-I interferons play a pivotal role is SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis whereby suppression of these responses is associated with poor outcomes.20 This is particularly concerning with respect to the injections.

…we present evidence that vaccination induces a profound impairment in type I interferon signaling, which has diverse adverse consequences to human health.

…in the case of SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine, unlike the immune response induced by natural SARS-CoV-2 infection, where a robust interferon response is observed, those vaccinated with BNT162b2 mRNA vaccines developed a robust adaptive immune response which was restricted only to memory cells, i.e., an alternative route of immune response that bypassed the IFN mediated pathways (Mulligan et al., 2020) (Extracted from Reference #3)

Since these pivotal interferons are suppressed in the context of the COVID-19 mRNA injections, what are the effects of their suppression on viral tropism in the context of an individual who is challenged with SARS-CoV-2 following injection with the COVID-19 injectable products? What would be the effects on the HIV-infected population? Some very relevant things to think about.

HIV-1 readily infects monocytes and macrophages, as does SARS-2.2122

Also, I don’t mean to be an alarmist, but there is a pre-print article online whereby the authors claim that SARS-CoV-2 infects CD4+ T cells.23 It's been sitting on the pre-print server for 2 years.

T helper cells are infected by SARS-CoV-2 using a mechanism that involves binding of sCoV2 to CD4 and entry via the canonical ACE2/TMPRSS2 pathway. Our model suggests the hypothesis that CD4 stabilizes SARS-CoV-2 on the cell membrane until the virus encounters an ACE2 molecule to enter the cell (fig. S11). This mechanism is similar to what has been described for HIV infection.

As the authors point out, this might explain the large number of reports of lymphocytopenia that have been filed to VAERS (N = 9,209; N = 285,479 with URF 31) and the dysregulation of inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients.

On recombination/in vitro genome assembly/infectious clone design

Recombination of viruses involves the co-infection of a cell by at least two viruses whereby during the replication process, the genetic materials of the two viruses recombine to produce a new virus with a mix of genetic components from each single virus. Interestingly, the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been hypothesized to be the result of a recombination event between a bat coronavirus and an as yet unidentified human coronavirus.24 It has also been hypothesized that the bat coronavirus in question, RaTG13, was a construct of man,25 thus, if this is the case, then if there was a recombination event, then it was the product of the combination of 2 viruses; one of which was made by man. That means, that the SARS-CoV- 2 virus is also man-made.

The in vitro genome assembly (IVGA) method utilizes special enzymes called restriction enzymes “to generate DNA building blocks that then can be stitched together in the correct order of the viral genome”. (From reference #3) Lab-made viruses are created by engineering a viral genome that involves adding or removing restriction sites: the sites where the DNA building blocks are stitched together. This IVGA method is used in order to make it easier to study viruses (aka: ‘facilitate antiviral testing and therapeutic development’ - from Reference #1) and the effects of specific mutations, for example.

Infectious clone design involves production of recombinant viruses whereby a double-stranded DNA copy of the viral genome is carried in a bacterial plasmid and delivered to cells by transfection26 to produce infectious virus. DNA is proofread when it is replicated so maintenance of high fidelity products is ensured.27

The technology is all (t)here. That’s the bottom line. Why wouldn’t they be using it? Did they use this technology to make a very dangerous, perfectly infectious clone (like, literally - no dud virions come from an engineered clone) that disseminated into the coronavirus ‘swarm’ to eventually naturally downgrade its dangerousness through mixing?

What a question.

By the way, a massive thank you to Jonathan (JJ) Couey, Mathew Crawford, John Beaudoin and Marc Girardot for the Thursday night chats. This latest one inspired me to include the aforementioned question in this article. It’s JJ’s idea, and after our conversation last night, I actually dreamed only about clones. It was like this matrix of puzzle pieces were floating around the dark matter of my subconscious waiting for me to put these pieces together. I didn’t manage to. Yet. But, this hypothesis of an engineered clone makes a lot of sense to me in light of the information we have to date.

In any case, without the original lab notes, as I have previously written that I would love to get my hands on, we will never know how this SARS-CoV-2 thing truly came about.

Let’s go back to the questions at the top of the article:

Question #1: If recombination (or in vitro genome assembly or reverse genetics system/infectious clone) techniques were used in a lab context to create a hybrid HIV-1/SARS virus (for example: a coronavirus with HIV peptides embedded in spike surface glycoproteins) then would phenotype mixing in vivo (in HIV-infected humans, say) allow for tropism enhancement of this hybrid virus?

Answer #1: I am certain that recombination techniques were used in a lab context to engineer what we know as SARS-CoV-2, and I think it does have HIV peptides embedded in its spikes. I would also say that phenotypic mixing is of great concern in the context of HIV-1-infected individuals. We have no idea what the the outcome of this mixing event would be, but we do know that HIV testing has been being done world-wide since the onset of this pandemoniumemic - for as yet, unknown reasons.

What do they know that we do not? It would fill up many more lab notebooks, I think.

Question #2: Could macrophages be the shared cell type for infectivity to enable phenotypic mixing?

Answer #2: Yes they could be. And monocytes as well.

Question #3: Would this hybrid be capable of infecting CD4+ T cells?

Answer #3: SARS-2 has been shown to do this already, so why not a new hybrid? (See Reference #23)

Question #4: Would this enhanced virus be readily transmittable to others via the SARS route (nasal/air)?

Answer #4: This is unknown.

It seems obvious at this point that SARS-CoV-2 is an engineered virus. That might sound definitive, so: good. I think it is.

I also think it is vital that some of these research questions are answered. And specifically, in individuals currently infected with HIV, we need to know what the chances of phenotypic mixing are? Since both of these viruses infect macrophages282930 then the possibility of phenotypic mixing is there. If receptors get exchanged, would this new virus be transmissible to others either by the same means as SARS-CoV-2, or perhaps by HIV, or both?

I have no doubt in my mind now that SARS-CoV-2 was engineered. I just don’t know why yet.

Additional supportive evidence will just keep rolling in.

Xuping Xie et al., An Infectious cDNA Clone of SARS-CoV-2, Cell Host & Microbe, Volume 27, Issue 5, 2020, Pages 841-848.e3, ISSN 1931-3128, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.004

Thi Nhu Thao, T., Labroussaa, F., Ebert, N. et al. Rapid reconstruction of SARS-CoV-2 using a synthetic genomics platform. Nature 582, 561–565 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2294-9.

Valentin Bruttel, Alex Washburne, Antonius VanDongen. Endonuclease fingerprint indicates a synthetic origin of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2022.10.18.512756; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.18.512756

https://www.etymonline.com/word/corona

Nathalie Chazal, Denis Gerlier. Virus Entry, Assembly, Budding, and Membrane Rafts. ASM Journals. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. Vol. 67, No. 2. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.67.2.226-237.2003.

Wang, Hao; Yuan, Zixuan; Pavel, Mahmud Arif; Jablonski, Sonia Mediouni; Jablonski, Joseph; Hobson, Robert; Valente, Susana; Reddy, Chakravarthy B.; Hansen, Scott B. (10 May 2020). "The role of high cholesterol in age-related COVID19 lethality". doi:10.1101/2020.05.09.086249.

Yuan, Zixuan; Pavel, Mahmud Arif; Wang, Hao; Kwachukwu, Jerome C.; Mediouni, Sonia; Jablonski, Joseph Anthony; Nettles, Kendall W.; Reddy, Chakravarthy B.; Valente, Susana T.; Hansen, Scott B. (14 September 2022). "Hydroxychloroquine blocks SARS-CoV-2 entry into the endocytic pathway in mammalian cell culture". Communications Biology. 5 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03841-8.

Hui Zhang, Hong Zhang, Entry, egress and vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2, Journal of Molecular Cell Biology, Volume 13, Issue 3, March 2021, Pages 168–174, https://doi.org/10.1093/jmcb/mjab013.

Illanes-Álvarez F, Márquez-Ruiz D, Márquez-Coello M, Cuesta-Sancho S, Girón-González JA. Similarities and differences between HIV and SARS-CoV-2. Int J Med Sci. 2021 Jan 1;18(3):846-851. doi: 10.7150/ijms.50133. PMID: 33437221; PMCID: PMC7797543.

Nieto-Garai JA, Glass B, Bunn C, Giese M, Jennings G, Brankatschk B, Agarwal S, Börner K, Contreras FX, Knölker H-J, Zankl C, Simons K, Schroeder C, Lorizate M and Kräusslich H-G (2018) Lipidomimetic Compounds Act as HIV-1 Entry Inhibitors by Altering Viral Membrane Structure. Front. Immunol. 9:1983. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01983.

Schoeman, D., Fielding, B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol J 16, 69 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0.

The HIV-1 env gene encodes the gp160 glycoprotein, which is subsequently cleaved into the envelope proteins gp120 and gp41. Pathogenesis of HIV-Associated Nephropathy. Michael J. Ross, Paul E. Klotman, in Molecular and Genetic Basis of Renal Disease, 2008

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/viral-tropism

Michael C W Chan et al., Lancet Respiratory Med 2020; 8: 687–95 Published Online May 7, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2213-2600(20)30193-4.

Paul T, Ledderose S, Bartsch H, Sun N, Soliman S, Märkl B, Ruf V, Herms J, Stern M, Keppler OT, Delbridge C, Müller S, Piontek G, Kimoto YS, Schreiber F, Williams TA, Neumann J, Knösel T, Schulz H, Spallek R, Graw M, Kirchner T, Walch A, Rudelius M. Adrenal tropism of SARS-CoV-2 and adrenal findings in a post-mortem case series of patients with severe fatal COVID-19. Nat Commun. 2022 Mar 24;13(1):1589. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29145-3. PMID: 35332140; PMCID: PMC8948269.

Puelles et al., Multiorgan and Renal Tropism of SARS-CoV-2. August 6, 2020. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:590-592. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2011400.

Bhatnagar J, Gary J, Reagan-Steiner S, Estetter LB, Tong S, Tao Y, Denison AM, Lee E, DeLeon-Carnes M, Li Y, Uehara A, Paden CR, Leitgeb B, Uyeki TM, Martines RB, Ritter JM, Paddock CD, Shieh WJ, Zaki SR. Evidence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Replication and Tropism in the Lungs, Airways, and Vascular Endothelium of Patients With Fatal Coronavirus Disease 2019: An Autopsy Case Series. J Infect Dis. 2021 Mar 3;223(5):752-764. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab039. PMID: 33502471; PMCID: PMC7928839.

Reagan-Steiner S, Bhatnagar J, Martines RB, Milligan NS, Gisondo C, Williams FB, Lee E, Estetter L, Bullock H, Goldsmith CS, Fair P, Hand J, Richardson G, Woodworth KR, Oduyebo T, Galang RR, Phillips R, Belyaeva E, Yin XM, Meaney-Delman D, Uyeki TM, Roberts DJ, Zaki SR. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Neonatal Autopsy Tissues and Placenta. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022 Mar;28(3):510-517. doi: 10.3201/eid2803.211735. Epub 2022 Feb 9. PMID: 35138244; PMCID: PMC8888232.

McFadden, G., Mohamed, M., Rahman, M. et al. Cytokine determinants of viral tropism. Nat Rev Immunol 9, 645–655 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2623.

Seneff S, Nigh G, Kyriakopoulos AM, McCullough PA. Innate immune suppression by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations: The role of G-quadruplexes, exosomes, and MicroRNAs. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022 Jun;164:113008. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2022.113008. Epub 2022 Apr 15. PMID: 35436552; PMCID: PMC9012513.

Boumaza A, Gay L, Mezouar S, Bestion E, Diallo AB, Michel M, Desnues B, Raoult D, La Scola B, Halfon P, Vitte J, Olive D, Mege JL. Monocytes and Macrophages, Targets of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: The Clue for Coronavirus Disease 2019 Immunoparalysis. J Infect Dis. 2021 Aug 2;224(3):395-406. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab044. PMID: 33493287; PMCID: PMC7928817.

Cui J, Meshesha M, Churgulia N, Merlo C, Fuchs E, Breakey J, Jones J, Stivers JT. Replication-competent HIV-1 in human alveolar macrophages and monocytes despite nucleotide pools with elevated dUTP. Retrovirology. 2022 Sep 16;19(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12977-022-00607-2. PMID: 36114511; PMCID: PMC9482235.

Gustavo G. Davanzo, et al., SARS-CoV-2 Uses CD4 to Infect T Helper Lymphocytes medRxiv 2020.09.25.20200329; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.25.20200329

Kozlakidis Z (2022) Evidence for Recombination as an Evolutionary Mechanism in Coronaviruses: Is SARS-CoV-2 an Exception? Front. Public Health 10:859900. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.859900.

Arumugham, Vinu. (2020). Root cause of COVID-19? Biotechnology's dirty secret: Contamination. Bioinformatics evidence demonstrates that SARS-CoV-2 was created in a laboratory, unlikely to be a bioweapon but most likely a result of sloppy experiments. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3766463.

The introduction of DNA or RNA into cells with the object of obtaining infectious virus is called transfection (transformation-infection). https://www.virology.ws/2009/02/12/infectious-dna-clones/

Bębenek, A., Ziuzia-Graczyk, I. Fidelity of DNA replication—a matter of proofreading. Curr Genet 64, 985–996 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00294-018-0820-1.

Asma Boumaza, Laetitia Gay, Soraya Mezouar, Eloïne Bestion, Aïssatou Bailo Diallo, Moise Michel, Benoit Desnues, Didier Raoult, Bernard La Scola, Philippe Halfon, Joana Vitte, Daniel Olive, Jean-Louis Mege, Monocytes and Macrophages, Targets of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: The Clue for Coronavirus Disease 2019 Immunoparalysis, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 224, Issue 3, 1 August 2021, Pages 395–406, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiab044.

Clayton KL, Garcia JV, Clements JE, Walker BD. HIV Infection of Macrophages: Implications for Pathogenesis and Cure. Pathog Immun. 2017;2(2):179-192. doi: 10.20411/pai.v2i2.204. Epub 2017 May 24. PMID: 28752134; PMCID: PMC5526341.

Zita Kruize and Neeltje A. Kootstra. REVIEW article. Front. Microbiol., 05 December 2019. Sec. Virology https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02828

Thanks, Jessica. Now we know why Luc Montagnier said that all the jabbed victims should be tested for AIDS. And as to why this virus was created, the billionaire psychopaths think we need to vastly reduce the population, and big Pharma wants to make hundreds of billions and doesn't care how many they have to murder to do it, and most politicians are narcissistic control freaks who have used fear to take away our rights.

So the injections might be a mass experiment of rolling the dice to see if injection induced spike might phenotype mix with HIV and create turbo HIV that might even be contagious like sars-cov-2? That would explain the paranoia in China about zero covid. I seem to recall that earlier this year a team of Chinese scientists also published on sars-cov-2 infecting CD4+ T-cell via something called LFA-1.

On another note, what the Boston U research makes me think of is the bivalent boosters. If the omicron spike is responsible for increased infectiousness of omicron and if pairing it with wuhan backbone makes it more deadly, is it really a good idea to start pumping out omicron spike in the bodies of injectees?

All these bad things bumping into each other seems...well....bad.